Jean Valjean was like a man on the point of fainting.

The Bishop drew near to him, and said in a low voice:—

“Do not forget, never forget, that you have promised to use this money in becoming an honest man.”

Jean Valjean, who had no recollection of ever having promised anything, remained speechless. The Bishop had emphasized the words when he uttered them. He resumed with solemnity:—

“Jean Valjean, my brother, you no longer belong to evil, but to good. It is your soul that I buy from you; I withdraw it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God.”

Man lives together in cities, in neighborhoods, in apartment complexes, but everywhere is alone. In 1690, an American neighborhood consisted of families who crossed an ocean to practice their faith together. In the 1940s, a neighborhood consisted of immigrant families who could reminisce together about the same Old Country. In 2022, what do we share with our neighbors? Maybe some weak commonalities: socioeconomic status, race, politics. We don’t share a faith. We don’t share a common culture. Many of us have never shared a meal with our neighbors, or even interacted beyond a quick wave as we pass one another by. Everyone is desperately alone, and seeking community. The more “fortunate” may seek that community in hyperspecialized online forums: Marvel fandom, Marx/Lenin fandom, Andrew Tate fandom. The less fortunate may find it in a gang. Getting shot beats dying alone. None of these communities can plausibly promise prosperity, even if they talk about it.

Suppose we, a group of good men, intentional Christians, became dissatisfied with friendship that exists primarily in a “group chat” or “Discord server.” We decide to move together to a neighborhood, near a church, where we can exercise our friendship and our faith together. We buy houses within walking distance of one another. It is not an easy or fast process, but it is clearly possible. Christians living together in a neighborhood sharpen one another, as iron sharpens iron. I myself can testify to this, as I have been fortunate to live in a neighborhood with other Christians due entirely to the grace of God.

If we are motivated and focused enough to achieve such a neighborhood, it is unlikely we will stop there. Over time the houses transform from debt into wealth. Our friendships transform as well: our Sunday night back porch conversation passes from consumption of news, movies, and books to the possibilities of creation and business. A few friends pooling their capital could build a profitable business venture (or five). This is an avenue worth considering today: increasingly we are pressured to give a “pinch of incense” at our office jobs to the HR department and its woke ideology. Increasingly, keeping our heads down is not an option. If we own capital, we need not fear being fired. A network of Catholic businessmen could take material care of one another no matter how “canceled” we are by secular businesses. Even better, this could be more than a story of survival. If we continued to expand, and raise our sons to be responsible stewards of a growing business empire, we could in short order be truly wealthy.

Twenty years ago this would have been fantasy, as all of our material needs and wants were well supplied by large multinational corporations. Today, incumbents in many industries are becoming victims of fragile centralized supply chains and have no succession plans for some of their most knowledgeable technicians. Many people have already experienced random shortages of groceries, electronics, and automobiles (my own mother-in-law has been waiting several months for a car she purchased). Europeans are staring down a cold winter with severe energy shortages. Meat prices are exploding. The city government of Jackson, Mississippi, recently announced that it is indefinitely unable to provide clean water. Enterprising individuals could realistically overthrow strong but fragile commercial incumbents and helpless government utilities. Pick what industry you want to go into: it could be disrupted by the mere fact of someone competent entering it.

Despite this pretty picture, there are two glaring flaws – for a Christian. First, this appears to be a worldly distraction from what Christ instructed us to do. We are to go and preach the Gospel. Christian neighbors building business empires together may win them independence from their enemies, and may even address the cascading industrial disasters above. But how is it going to bring a single saint into the Kingdom? An even more worrisome problem is that such a Christian neighborhood may thrive in a material sense and not a spiritual one. Wealth is very much a temptation to vice. If we use the same capitalist playbook and achieve the same successful results, how can we avoid the same greed, cruelties, and pathologies that occurred the first time around? The answer to both questions could lie in the attitude we have toward our employees. Instead of simply seeking to buy labor power on an open market, we shall buy souls. We shall not simply pay wages as just compensation, or as replenishment for expended energy, or even as investment to create a more capable employee. We are seeking to use wages to bring that person to Christ.

What does that look like? We can learn from two historical models of buying souls. The first is patronage. Give a man a job, and you secure his loyalty. Buy enough men, and you have the power to achieve a purpose. Tammany Hall (a name now unfortunately sullied in the public imagination) was a patronage network dedicated to buying men and steering them to vote for Democrats in New York State. How many of us only know of it from the caricatures of cigar-smoking, manipulative political bosses in Miracle on 34th Street and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington? A more useful character for our study is “Big Tom” Foley, a successful saloon owner and Tammany Hall operative who funneled his wealth into buying men. Multiplying his talents was not an end in itself, but a means for caring for people in the name of his master. Young men interested in a political career would seek employment from Foley to execute “contracts,” odd jobs meant to strengthen loyalty to the Tammany Hall machine: “An assurance to a local undertaker that Tammany would pay for a loyal Democrat’s funeral even if his family could not, a discreet visit to a brothel to warn of an upcoming police raid or to police headquarters to ease business-cramping parking restrictions in front of a liquor store belonging to a heavy campaign contributor.”1

It may be a shrewd business decision to influence a corrupt police force to favor a “heavy campaign contributor,” but why should Foley pay for the funeral of a penniless man? For that matter, why conduct this business by greasing the palm of every idle troublemaker who stops by? Surely a small, dedicated staff could do all of these things for less overall cost. The answer is that Tom Foley was buying men. His wealth was not for his own enjoyment, but for a higher cause: The New York State Democratic party. His “contracting” operation recruited Alfred Smith, who would go on to become governor of New York for four terms and the first Roman Catholic to be nominated for the Presidency. It also brought consistent electoral victories. Robert Caro writes of Foley:

Although his saloons thrived, he was to die a poor man, their profits trickling, along with the payoffs and the campaign contributions, through his fingers into those of his constituents. The only payment he ever asked for the favors he dispensed was a straight Democratic vote–and so heartily were his constituents willing to make this form of repayment that his district regularly rolled up Democratic majorities that made him the most powerful district leader in the city.

Tom Foley was a man who sold all he had and gave to the poor. Unfortunately, Tom Foley did not ask for enough from the people he paid. Though Tammany Hall had enough loyalty to regularly win elections, this did not translate to effective governance. So many government employees were employed only as patronage, and not because of their ability to do the work, that little was accomplished at much expense. Caro reports that during the mayoral reigns of Tammany Hall creatures “Red Mike” Hylan and Jimmy Walker, the New York City budget grew from $240 million to $632 million. The number of city employees doubled and their salaries tripled. The construction of the Independent Subway System cost double what experts estimated due to rampant incompetence and graft. Many city “engineers” did not hold even a high school diploma. Robert Moses’ prolific career in NYC parks service began with brutal destruction of Tammany Hall patronage jobs.

The patronage system arguably still exists today. Malcom Kyeyune propounds a theory that diversity, equity, and inclusion administrators are Democratic party patronage for loyal college graduates and activists. He quips that “the best way to defeat revolutionaries is to give them a job.” President Biden’s recent student loan forgiveness is another recent example, literally buying loyalty from a demographic on whom he depends. That said, no one seriously believes that DEI functionaries or extraneous college diplomas are making positive contributions to the efficiency, costs, or quality of any products. They are certainly not strengthening organizations as a cohesive unit. Therein lies the limitation of patronage: Jesus does not ask for something so paltry as a vote. He wants all your heart, all your mind, all your soul, and all your strength.

We must look to a more mature model of buying souls. For this, we could look to early capitalism in Rochester, NY. The City of Rochester in the early 1800s was built on a symbiotic relationship between grain farmers and manufacturers. Grain farmers would sell their grain to the flour mills and spend the money on manufactured wares built by craftsmen in the city. In small shops, there was not a strong distinction between residential and commercial. A master craftsman not only lived with his family in his workshop, but with the craftsmen he employed as well. This was from a Puritan attitude that young, unattached men should live under the care of a responsible family rather than independently. When a group of boys and young men were found to be ice skating on the Sabbath, a newspaper described it as a “great shame and disgrace of their parents and masters” (emphasis mine). A pair of young newlyweds described in a letter home “our family together which consists of seven persons,” implying extended family and employees.2 These families lived together, worked together, and drank together (in moderation) during the workday.

Christian businessmen do not necessarily need to bring all of their employees under their own roof, but the attitude towards one’s employees is worth considering. This is not a relationship of atomized individuals trading labor for wages, talking of nothing but business and the weather. These are men with a stake in one another’s salvation, nearly as strong a stake as one’s own blood relatives. The wages are not just for the sweat of the man’s brow, but for his soul. This is not simply an interesting stratagem for evangelization and the promotion of public virtue. It is the economy, rightly considered.

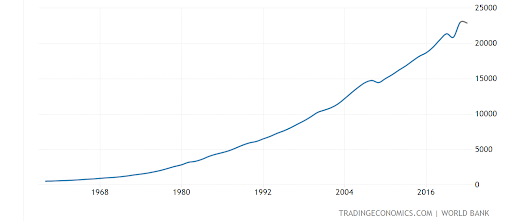

What does it mean for the economy to be “good?” GDP, even if it is an objective measurement, is not a very good perceptual one. Does the graph of GDP in the United States over time below match with your perception of the economy over your lifetime? I suspect none of the popular economic talking points do a good job of leading to an economy that is perceived as good: wealth inequality, presence or absence of single-payer healthcare or welfare state or amount of regulation. Pursuing any of these aims has objective material consequences, but they can also all be optimized without regard for the well-being of the people involved.

That is not a hot take in 2022. Any Marxist or Distributist or localist or seed oil disrespecter or Chestertonian or Belloc-ian or Wendell Berry-ian or Ilich-ian or @WrathOfGnon-ian could tell you the same thing. The take is that Rochester history shows us the precise moment, as if in a petri dish, where the capitalist economy went from human-centric to production-centric, and the direct consequences. The city was fast growing, from 700 to 7,000 people between 1817 and 1826, rendering its “village” charter wholly inadequate to govern the populace, which was divided between a small number of capitalists and a large number of laborers and craftsmen. Many of the laborers were transient. One newspaper editor quipped that 120 men left Rochester and 130 men entered it every day. The number of people, their velocity, and the amount of economic opportunity created definite incentives toward individualism. An enterprising man could fold good workers into his network, building and replenishing his community. But that depends on the network being a network of souls and not just of labor power and capital.

Unfortunately, as business operations grew, capitalists gave into the temptation to specialize. Small “family” shops grew until the patriarch could not give spiritual or even managerial attention to everyone in them. Capitalists moved their nuclear families into homes away from their shops, and laborers moved into flophouses and apartments. Casual, moderate social drinking within the workplace disappeared to re-emerge along class lines. Capitalists embraced temperance to keep their heads clear enough to juggle more and more materials and labor. Laborers drank heavily on their own time, leading to an increase of noise, crime, and dissipation.

Businessmen were no longer in the business of buying souls, only labor power. Laborers were no longer invested in a family, only a “job”. The consequences reached far beyond the monetary. Voting rights, initially granted only to property owners or laborers who provided some material service to the town (such as building roads), were extended to short term transients with no such investment. The growing vice of alcoholism was suddenly impossible to address by political means, as any politician who hoped to win a popular vote could not risk offending a large alcoholic labor force. A business which wanted to promote virtue would be buried by its competitor who did not care. This led to violent political feuds as principled Christian activists could not defeat, through votes or money, the vices they hated so much. More materially efficient business operations were a direct causal factor in the spiritual decline of Rochester.

This political stalemate was resolved by a Christian revival led by Presybterian evangelist Charles Finney. He preached individual moral responsibility and public repentance to the Calvinists throughout Rochester, convincing them to choose of their own accord to forsake the bottle and serve the LORD. Or if their own accord was not enough, then the peer pressure of their congregation or the haranguing of their wives. Many men returned to Christ because Finney convinced their wives first. An anonymous critic calling himself Anticlericus cursed Finney:

He stuffed my wife with tracts… nothing short of meetings, night and day, could atone for the many fold sins my poor simple, spouse had committed.… peace, quiet, and happiness have fled from my dwelling, never, I fear, to return.

The product of this conscious individual effort at scale was to be, Finney argued, a thousand years of prosperity on this Earth. For a time, people were motivated to seek it, energetically proclaiming the kingdom of God and rigorously sharpening one another in virtue, “as iron sharpens iron”. The political turmoil was quelled for the moment, as the temperance movement now had enough political support among the capitalists and labor combined to rescind liquor licenses. Grocers who had flouted liquor laws for competitive advantage now volunteered to pour their whiskey into the Erie Canal. For the moment, the most important issue was addressed as well: people had returned to Jesus. Yet the family employment structures did not return, which meant that Christian virtue could only be sustained as long as the mass enthusiasm for it was sustained. The physical isolation between capitalists and labor remained, and as the enthusiasm for the Great Awakening waned, the spiritual isolation returned.

Whoever brings a sinner back from his wandering covers a multitude of sins, even those of capitalism. But a stronger Christian culture can be built at the inflection point of capital accumulation: where the market efficiencies of centralization are balanced with concern for its participants’ spiritual well-being. This is a strategy we can use. We can buy souls not through a mere bribe for loyalty, nor through an enthusiasm lasting only until it burns out, but through inclusion in a material, social, and spiritual family. It means a network of Catholic businessmen who are doing more than building an economic fortress to hide themselves as society collapses. They are using the gifts God has given them to bring non-Christians into the fold. Into a family. Into the Body of Christ!

As Gaston Nerval points out, civil rights law intentionally discourages for-profit businesses from having any salutary spiritual purpose. Legitimacy of this model will not come from the imprimatur of a hostile government, but from the thriving of the men who live and work within it. Consider an unattached man seeking a job from a Christian businessman. One such “Christian” businessman sees him as mere atomized labor power to be ignored at the close of business. Another takes him in as a sojourner, clothes him, feeds him, and makes him like a son (and not just a son of a man, but of a son of God!). Will he be so quick to complain to our enemies? It is not risk free. Evangelization never is. But it is a strategy that did work, when men who used it did not realize what they were doing.

Building Christian community is our great work. It is the salve for men and women despairing in quiet isolation. Yet it is a fraught process. A community can easily exclude those who need it. There are so many worldly details to be accounted for and so many earthly measures of success that are bound up in it that forgetting about Jesus Christ, the reason for our work, is a persistent threat. We must remember that every good thing we have comes from God. We are stewards of the wealth He has entrusted to us for our mission to bring the Good News to the world. If He has given us five talents, we should reap five plus five talents worth of souls. If we have ten talents, we should reap ten plus ten. We know men’s souls can be bought. Let us buy them for the LORD.