Bless the Maker and His water.

Bless the coming and going of Him.

May His passage cleanse the world.

May He keep the world for His people.

Dune, Frank Herbert

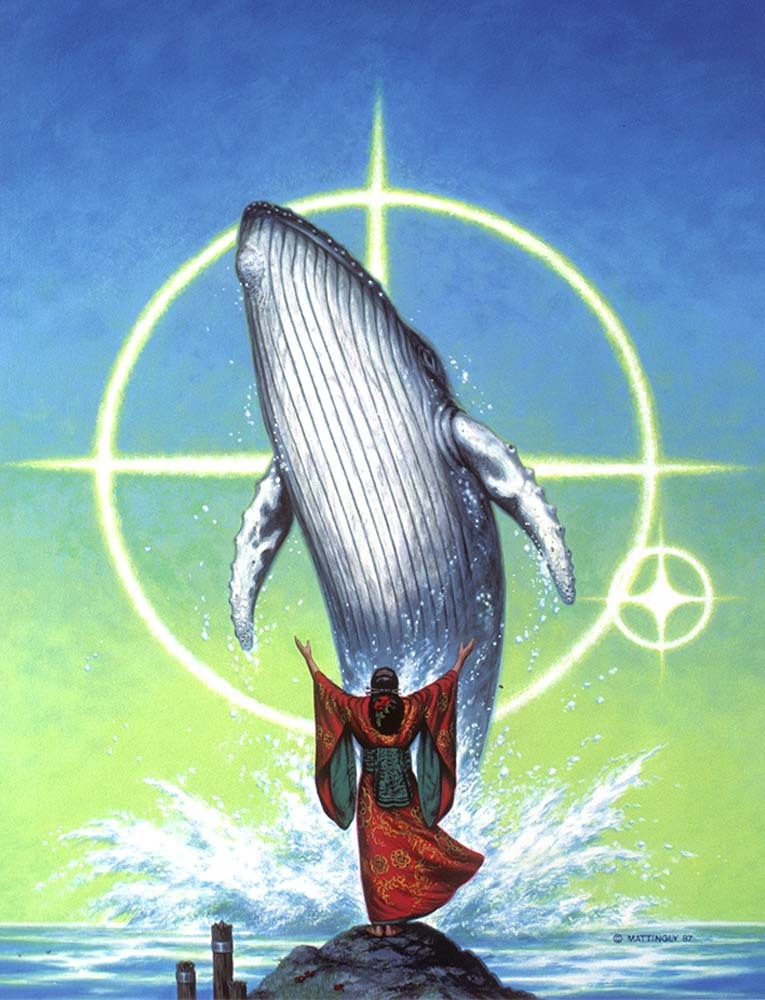

Moby Dick is not a Christian novel. The bulk of the book is spent at sea, on a ship under the command of a Miltonian Satan at war with God. But the arresting image of Captain Ahab’s hubris and the unconquerable force of nature Who punishes it has tended to overshadow the true focal point of the story: its narrator, Ishmael, and his conversion to the worship of the Whale.

Ishmael’s relationship with the harpooner Queequeg seems at first glance to be commendably American in its gregarious ecumenism. After an initial shock at realizing he is to bunk with the tattooed giant, he reasons “better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian”. This equanimity extends to participating in Queequeg’s offering to his idol Yojo– in violation of the biblical stricture of Acts 15:29, which admonishes believers not to partake of food sacrificed to idols. Shortly thereafter, Queequeg informs Ishmael that Yojo has chosen a ship for the pair, and has designated Ishmael to find it. By his participation in the idolatrous rites, then, Ishmael becomes an apostle of an alien god.

The crew of the Pequod is full of pagans, especially the mysterious figures of Fedallah and his companions, who emerge from solitude only to battle the whales. The imagery of the voyage grows steadily more infernal as it progresses, until the Pequod is rendered a hell-ship, plunging through an abyss illuminated only by its own sinister furnaces. The crew are swept up and consumed by Ahab’s vendetta, leaving Ishmael as the sole survivor.

It is thus possible to read Moby Dick as a warning against the dangers of dabbling in pagan rites. Yojo’s commission to Ishmael ultimately serves only to make him a witness to an act of divine punishment, as God smites Captain Ahab in his pride just like his biblical namesake. Both these interpretations– Ishmael as Transcendentalist and Ishmael as Puritan– neglect that Ishmael openly declares himself a committed pagan.

At the beginning of the novel, we encounter “Ishmael” after the end of the voyage he recounts. Since its conclusion, he has clearly spent many more years hunting whales: by the time we meet him, he is probably one of the foremost experts in the world. The oft-derided interstitial chapters are an encyclopedia of the whale, and not merely its material characteristics. They are meditations on its theology.

Probably the most important of these is the tale of his visit to the island of Tranque, whose inhabitants have fashioned a shrine around the bones of a beached whale:

The ribs were hung with trophies; the vertebrae were carved with Arsacidean annals, in strange hieroglyphics; in the skull, the priests kept up an unextinguished aromatic flame, so that the mystic head again sent forth its vapory spout; while, suspended from a bough, the terrific lower jaw vibrated over all the devotees, like the hair-hung sword that so affrighted Damocles.

Moby Dick, Chapter CII

Ishmael’s devotion to this sun-bleached deity is such that he spends many hours delving in its cavernous interiors, measuring its every dimension and inscribing them on his flesh. The whole story, in other words, is being related to us by a tattooed priest of the whale.

The whale is not exactly God, but it is certainly a god; a vast, omnipotent, and terrifyingly embodied Power. Ishmael’s tale shows early glimpses of what would come to be called cosmic horror, as he describes the whale descending to the bottom of the abyssal oceans, rooting about the unknowable pillars of creation. It is a being of inscrutable purpose and ineffable knowledge. To contemplate the whale is to confront one’s own insignificance: the very essence of cosmic horror*.

To Captain Ahab, the whale is an object of hatred, and to his motley crew of pagans a mere source of profit. It is significant that the whole crew, even the devoutly Christian Starbuck, is swept up into Ahab’s quest for revenge. Since their relationship with the whale is merely economic they have nothing with which to oppose the searing rage of Ahab. Ishmael, alone among the crew of the Pequod, worships the whale, and Ishmael alone is spared. To the extent that he bears a message, it is simply that Leviathan merits worship. Ishmael is an initiate into the mysteries of the whale, rather than an evangelist. His vocation is priestly, as distinct from prophetic.

Whaling was the last fair fight in nature, where man could strike out into the wild with all the technology and advantages he could possibly bring to bear and still face no better than equal odds of success or even survival. For Ishmael, hunting and even killing the whale is an act of worship. The hunt has the character of a sacrament, and should Leviathan prove victorious Ishmael would be the first to proclaim that its judgment was true and righteous altogether. This is the lesson he takes from the whalers’ church in the town of New Bedford, itself as much a temple to the whale as to God. Their conception of God has insensibly become mingled and interchanged with the whale by their constant contemplation of and contention with it. Their devotion has passed from admiring the whale as a creation of God to appreciating God as an aspect of the whale. The sailors who perish in battle with the whale are sacrifices to its majesty. Ishmael would have been horrified at the technological developments which were already beginning to tip the balance of the struggle decisively in favor of man by the 1840s. If the whale was robbed of its sacrifices, it would be robbed of its glory.

The proper attitude toward creation is awe. In his recollections, we can see that Ishmael’s encounter with Leviathan has awakened him to the mysticism of the commonplace. Ishmael, like the people of New Bedford, has found God in the whale. When we leave behind this ancient mariner with the names of God inscribed on his flesh, it should be with renewed wonder at the artistry of the Artist.

*Consider also the Lovecraftian fate of Pip the cabin boy, who when rescued after some days lost at sea has been driven mad by his encounter with the infinite.

1 thought on “The Great God Leviathan”