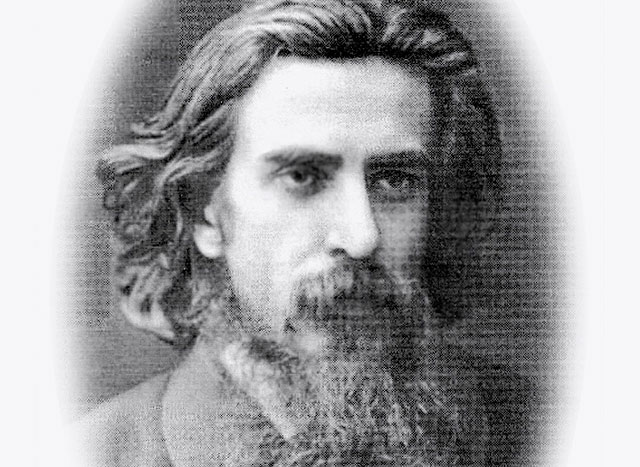

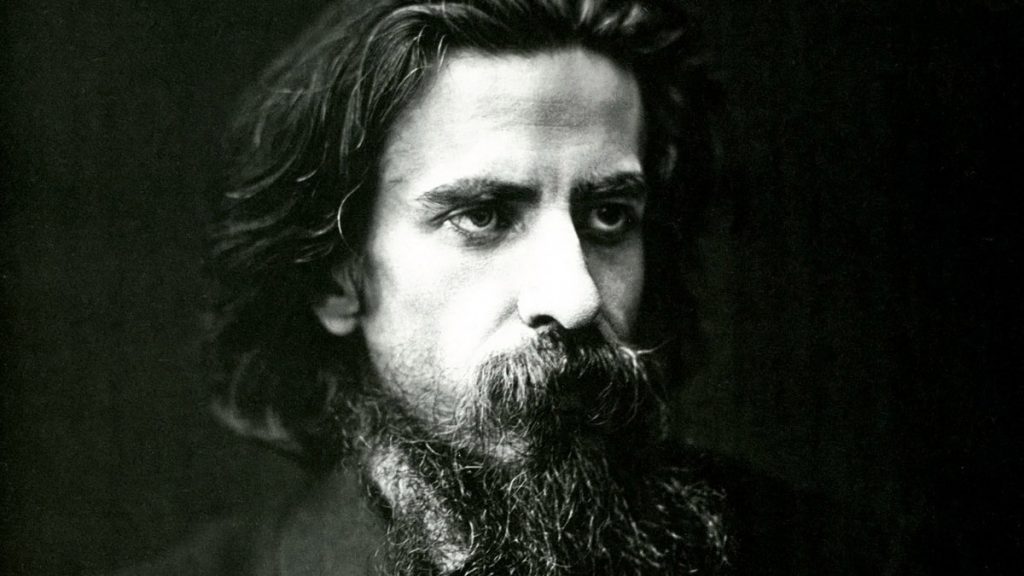

Depictions of anti-Christ abound in Christian fiction. The most famous in recent times is the “Left Behind” series, where a sinister dictator ushers in a world government through the United Nations. There is also Robert Hugh Benson’s Lord of the World, a particular favorite of Pope Francis. But their progenitor is to be found in “A Short Story of Anti-Christ” by the Russian mystic Vladimir Soloviev: a short, simple work whose echoes resound through Christian writing of the twentieth century.

Soloviev gave us the figure of a superman, gifted and talented far beyond all other men, able to unite them by spellbinding oratory and a compelling new vision of the good. His only flaw, if indeed it is a flaw in so remarkable an individual, is a lack of humility, an unwillingness to bow before Jesus Christ. Despite his historic success in establishing world peace and organizing a materially just society, this unwillingness puts him at odds with the last few faithful Christians: a Pope, an Orthodox monk, and a Protestant doctor. These lonely believers refuse to do homage to the lord of the world after watching him buy off their co-religionists. The Pope and the monk are themselves struck dead by “heavenly fire” called forth by the superman’s henchman, himself the inspiration for C.S. Lewis’s “materialist magician.” In the end, the faithful Jews of Jerusalem rise up to overthrow this false Messiah, and the world ends with a great conflagration to greet the second coming of Christ.

In the first place, Soloviev’s foresight deserves to be recognized. Writing in 1900, he appears to have already sensed both of the calamitous wars which would wrack his homeland over the next century. At this remove, it is fair to say that he predicted the trajectory of Christianity with remarkable accuracy. The mainline Protestant denominations have all but evaporated, and the last believers on Earth may very well be a Pope, a starets, and an austere Calvinist professor. Soloviev’s anti-Christ, like Benson’s Felsenburgh, wins his authority by popular adulation. The masses he has redeemed from war and hunger positively worship him with a fervor that cannot precisely be called idolatry, for his acts are the acts of a god. Christianity itself faces a dark night of the soul. All believers are forced to confront the question of whether they truly desire Christ Himself: not for any hope of material prosperity, earthly happiness, or even spiritual consolation. For the great majority, the answer is no. If anti-Christ can deliver both earthly and spiritual bread, they have no need of his predecessor.

Every dictator, every popular leader, possesses some attributes of anti-Christ as understood by Soloviev. The twentieth century was little other than a parade of them. It is easy to recognize the dismal pattern of promised utopias ruined in the construction, resulting instead in ever-more-terrible machines for human immiseration. When writing about anti-Christ, the Christian authors of the twentieth century imagined some future dictator who would really deliver on his promises, who could really turn stones to bread. But now, at last, we are taking our first tentative steps outside the long shadow of the Second World War, and the even longer shadow of the first. The dictator anti-Christ no longer accurately represents the challenges of modernity.

This brings us to Zero HP Lovecraft, the pseudonym of a tremendously gifted amateur writer of horror fiction. Like his namesake, Zero is deeply uneasy with the philosophical underpinnings of modernity and what they imply about our place in the universe. Though he is not a Christian, his 2018 story “The Gig Economy” presents a new vision of anti-Christ not as a man, but as a system. Its threat, in his view, is less world government than world optimization. He identifies “Mammon” with the relentless and remorseless quest for efficiency until algorithms and supply chains overrun the world. His narrator inverts Lovecraft to say “The most menacing thing in the world is the ability of the cloud to correlate its contents.” The final outcome is a world where all activity which does not directly contribute to the maximization of GDP has been abolished.

It has become a truism to say that Huxley’s prophecy of a world deadened by hedonism is more accurate than Orwell’s boot stamping upon a human face forever. But at present, there seems only a very remote possibility that the reign of anti-Christ will usher in a material utopia. Zero shares Orwell’s insight that immiseration is not an unintended consequence but the explicit, stated goal of contemporary progress, as events of the last year made terribly clear. Once soma has been invented, the people can be kept docile; and if they can be kept docile with plenty, they can be kept docile with nothing. Today, Soloviev would fear that genetic engineering will replace humanity with a race of demigods ten feet tall. Zero fears that it will replace us with dwarfs who do not sleep and can code JavaScript on four hundred calories per day.

The new anti-Christ is not an individual person, unless as the mouthpiece through which Mammon speaks. There is no need for a malevolent, guiding intelligence behind the curtain; his reign is the natural consequence of billions of individuals working to increase efficiency. This increase is effected by the paring away of extraneous processes and efforts. As the automobile was a more efficient horse, the slave of anti-Christ will be a more efficient man. The future toward which this anti-Christ is working no longer has any need for invention or genius: existing processes are sufficient for every necessary purpose, and there remains only the task of incrementally improving them. The extraneous processes of humanity – private property, leisure, art, even reproduction – are being steadily removed. The anti-Christs of the twentieth century sought to be worshipped instead of God. The anti-Christ of the twenty-first seeks to eradicate the capacity for worship altogether.

3 thoughts on “The New Anti-Christ”