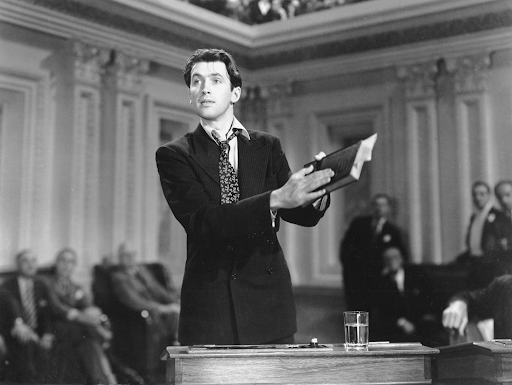

The high-water-mark of American civil religion was probably the 1939 film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Jimmy Stewart plays the titular Mr. Smith, appointed by a feckless governor to fill an empty Senate seat. Once in Washington, Smith is forced to confront a corrupt political machine centered, to his horror, on his childhood idol Senator Joseph Paine. Smith’s dedication to America’s founding principles is so absolute that it overcomes his enemies. I can say without exaggeration that he is presented as a liberal-democratic Christ, and even the soulless Senator Paine is moved to repentance by the sight of his crucifixion. Smith gets girl, villains exit pursued by bear, credits.

This film may not be the highest artistic expression of the American ideal, but as a portrayal of what this ideal meant when it was still more or less universal it is unparalleled. Mr. Smith is the perfect American, a philosopher-citizen beholden only to his own sense of justice but also firmly anchored in good old horse sense. In 1939, though the hegemony of men with WASPy names like “Cordell Hull” and “Homer Cummings” remained firm, America was headed in the direction of an expansive if paternalistic concern for minorities. This movement was driven precisely by devotion to the abstractions of the American ideal.

The WASP hegemony has long since been shattered. In the context of the multipolar, multicultural America that exists today, it is worth re-assessing Mr. Smith, especially against his foil Sen. Paine. Smith’s greatest virtue, after all, is his integrity, but sometimes integrity is merely a nicer way of saying callowness. Smith positions himself against a construction project backed by Paine and his cronies out of his sense of justice, as it is wrong for men in positions of public trust to take advantage of their authority to enrich themselves. Paine, in Smith’s view, has gone to Washington to loot the treasury for the benefit of the people who put him in office, a small network of powerful individuals from his state. Paine’s loyalty, in other words, is to people, while Smith’s is to ideals. Paine’s corruption is known and circumscribed by the loyalty he owes to his backers. He can be relied upon to direct as much federal money as possible to his state: directly benefiting his backers first, of course, but such windfalls can hardly help benefiting a larger fraction of his constituents. If a dam is to be built, it can only be built in a limited and predictable number of places. The corruption or manipulation of Sen. Smith only ever awaits encounter with a subtler or more devious intelligence. By rejecting the embodied interests represented by Sen. Paine, Smith makes himself vulnerable to the faceless ones. Does the strident idealism of an Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez make her harder or easier for party leadership to control?

The framers of the American Constitution spent a great deal of time and thought devising ways to prevent the emergence of “faction.” This was a reasonable reaction to the memories of the English Civil War inscribed on their bones, but faction itself is not an unalloyed evil. Faction can exert a moderating influence on the naïveté of individuals, especially idealistic individuals. The obligations of political leaders to specific interests organically tend to check each other. Put cynically, you can’t bribe all of the senators all of the time.

On a deeper level, the effort to eliminate faction was doomed from the outset to fail; factions naturally emerge among people with common interests, and without common interests what is a republic? Many of the difficulties before the American republic stem from the emergence of the federal government as a faction in itself, with very little opposition of the sort provided by Sen. Paine and his state-level political machine. Today, the concept of the political machine is well worth revisiting, as they constitute a possible avenue for restoring some measure of subsidiarity against the crushing, homogenizing solidarity dominating American politics.

Paine and the machine behind him stand for an older form of politics based on patronage. Historically, this form of politics has been described by various disparaging terms such as “political machine,” “racket,” or “mafia,” but patronage is simply a formal way of describing informal networks of relationships centered on powerful individuals: loyalty flows up, favors flow down. It is both natural and good for the powerful to exert themselves for the benefit of those who look to them. This is noblesse oblige, not corruption!

It was only under the WASP ascendancy that “looting the federal treasury” was regarded as a bad thing, a state of affairs upon which we may look back with fondness but which must be recognized as a brief and anomalous period in history. They were perhaps the only ruling class in history who saw the telos of politics as “to secure the blessings of Liberty” rather than “to look after our own.” More than half a century of civil rights law and jurisprudence has made it all but illegal for certain fractions of the population to look after their own. Since favors cannot be dispensed, loyalty serves no purpose, and networks disintegrate. Power can only be exercised outside the law, and that means it can only be exercised by the wicked.

We could while away a few enjoyable hours imagining means of diluting the power of the federal faction: reducing the annual Congressional session to 90 days (which was sufficient for the Civil War), requiring members of Congress to spend at least half the year in their own districts (which would make it harder for lobbyists to influence them all from a single K Street office), and of course repealing the disastrous Seventeenth Amendment. But it would be far more productive to turn our attention instead to local politics. Your last local school board election, for example, was probably decided by a margin of less than a thousand votes. This is not outside the realm of possibility for a confederation of a few churches to influence decisively, but it will require the establishment of new patronage networks: small, to begin with. The first rule of politics is to reward your friends and punish your enemies. Punishment is currently beyond us, and will remain so for the foreseeable future, but if you want to know who your friends are and how to reward them you could do worse than perusing the back page of your church bulletin.

Let us not mince words. If “network” means anything for us, it means “people who can be trusted,” and specifically people who can be trusted to keep a secret. “Favors” means “money,” and specifically money I am free to disburse to the people who ask it of me.

We may already have a foundation for this kind of project before us in the form of the Knights of Columbus. I have in mind a sharper, leaner, meaner Knights, where dependable men exchange bulging envelopes of murky provenance in rooms hazy with cigar smoke, a smudge to repel the prying eyes of women. So let us bid a fond and reverent but definite farewell to Mr. Smith, and consider instead for our model Auda abu Tayi from Lawrence of Arabia:

I carry twenty-three great wounds, all got in battle. Seventy-five men have I killed with my own hands in battle. I scatter, I burn my enemies’ tents. I take away their flocks and herds. The Turks pay me a golden treasure, yet I am poor! Because I am a river to my people!

4 thoughts on “Farewell Mr. Smith”