When Lot moved with his family to live among the Canaanites at Sodom, he wanted not for reasons. The lands surrounding the city provided superior pasture. His own herds were too large to graze with those of his uncle Abram in any case. The city had strong walls, the occasional military defeat notwithstanding. What if the citizens had strange ways? Abram had been growing increasingly fanatical for some time, and a great city could not help but play host to exotic practices. In the final reckoning, he and his family had prospects, but only in the city. He wished Abram well in the wilderness.

Over the following years, Lot’s calculations were borne out. His herds burgeoned and increased, and before long he was numbered among the most prominent elders of the city. In a future struggle, he would himself have been able to come to the king’s rescue. Lot’s family prospered, and they were not alone: all around him, he saw only growth and flourishing. The ways of the city, exotic though they might have been in some respects, were self-evidently superior. He only hoped that Abram, or Abraham as he was calling himself these days, was doing well. He’d heard his uncle was experiencing some domestic troubles.

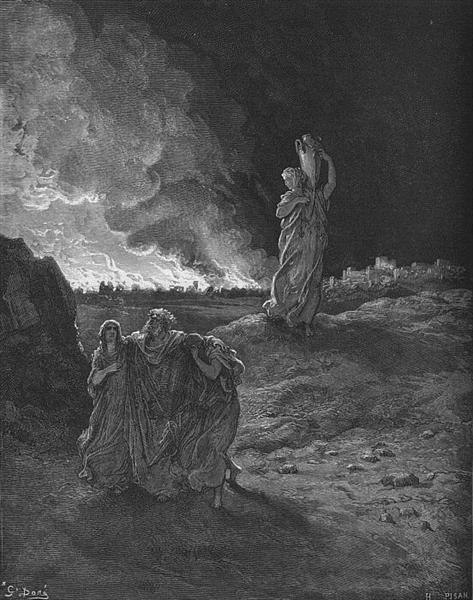

It was not until the destruction of the city that Lot realized its depravity. The messengers appeared, and suddenly there was a screaming mob at his door, and in his panic he offered the mob his daughters. At the time, this had seemed a perfectly reasonable thing to do – itself a horror he would not appreciate until it was too late. The messengers urged him, and finally seized him bodily, all but dragging him from the city with his family. But Lot’s wife behind him looked back, and she became a pillar of salt. So, in their own way, did his daughters.

Tobit did not move to the country of the Assyrians by his own choice. Though he, alone among his family, had refused to sacrifice to Baal, he was caught up in their shared disaster. There, too, he alone remained faithful to the Law, and for a time he was even permitted to prosper. He rose as high in the world as he was ever likely to do, and became a trusted servant to the king.

But the times changed – or Tobit did – and it fell to him to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and bury the dead among his people, though it was forbidden. What property he had acquired was taken away, and he was made all but destitute with his wife and son. In the course of these labors, he was stricken blind and left, helpless, to subsist on what his wife could earn.

Convinced that his life was approaching its end, Tobit entrusted his son with two treasures: a sum of money, and the Law of God, in the service of which he had experienced nothing but pain. But the Law would prove the more valuable by far. Armed with it, Tobit’s son returned with a bride saved from a demon and a cure for his own blindness, in addition to the money for which he had set out. Tobit would live to see his son raise sons of his own, and their faithfulness prepared them to flee Nineveh when warned by the prophet of God.

We are often confronted unawares with chances to show what we actually value, rather than what we merely profess to value. Only rarely is the stark alternative of apostasy or death presented. Salvation or damnation usually hinges on a succession of choices no more consequential than where or on what to spend small amounts of time and money. If we truly value a thing, we will find that time and money appear almost to set themselves aside for it. We may be surprised to find after decades that our painstakingly cultivated habits are those of worldliness, and that we are no longer capable of giving them up. Those habits are easy to acquire, because they are all around us. They can only be combatted by habits of spirituality and asceticism, which are not.

The vision of Tobit was not clouded by worldly success. He did not fear to endure privation for the sake of God. Material prosperity signifies accommodation with the existing order. God-fearing men are not found seated at the gates of Sodom.

Lot made his accommodation, and grew wealthy. Tobit did not, and suffered. But Tobit kept his family, and saw them preserved from destruction. They, after his example, were willing to leave their wealth behind when called – to do what Lot could not, save by the intercession of Abraham. Sometimes this may mean only a small sacrifice, that one will never advance further in the world. Sometimes it may mean more.

Viktor Frankl wrote of the Holocaust that “on the average, only those prisoners could keep alive who, after years of trekking from camp to camp, had lost all scruples in their fight for existence; they were prepared to use every means, honest and otherwise, even brutal force, theft, and betrayal of their friends, in order to save themselves. We who have come back, by the aid of many lucky chances or miracles – whatever one may choose to call them – we know: the best of us did not return.” One such was St. Maximilian Kolbe, who offered his own life for that of a stranger in Auschwitz. If circumstances become intolerable, they cannot be tolerated. God-fearing men will then be found in the lowest strata of society. The sphere of action may be constrained until only martyrdom, red or white, remains. In the words of Sidney Hook, “sometimes the worst we can know about a man is that he has survived.”

1 thought on “Where Your Treasure Is”