If there really is just one philosophical problem of consequence, suicide is an admission that one has failed to solve it. For an artist or philosopher, this failure has special significance. To commit suicide is to repudiate the whole world, of which one’s work is surely a part.1 It is quite a different matter from St. Thomas Aquinas’s “so much straw,” or the seaside pebbles of Isaac Newton. I am concerned not with a genius’s frustration at being unable fully to express the truths he understood, but with a flight from the world out of despair. Ambiguous cases of a prolonged life in misery, or slow self destruction, do not necessarily count. The suicide of an artist must be a willful action with death as its only foreseeable outcome (and, of course, an artist’s not committing suicide is no guarantee that his work has any special value). Consider the example of David Foster Wallace, who perished, like Onan, through an excess of self-knowledge. There is also Kurt Cobain, whose music, in retrospect, makes his suicide seem all but inevitable. And it is yet to be seen whether Jordan Peterson, grappling with the failure of his project to rationalize Christian morality, will kill himself or find a home in the Orthodox Church. Suicide means that the artist saw nothing worth living for. He found among the truths he understood nothing that could sustain: ultimately, his work could not give life. One should therefore be wary of loving the art of a suicide, because the artist did not.

A special case, if not quite an exception, is the Japanese author Yukio Mishima, whose body of work is almost explicitly a prolonged suicide note. His fiction, like Dostoevsky’s, abounds with suicide, though unlike Dostoevsky’s it treats suicide as an object for adoration, not horror: the final, ecstatic glory of a meteor blazing through the heavens. Part of this is the result of his situation within the Japanese artistic and cultural tradition, where suicide is attended by a semiotic entourage as long and diverse as it is alien to Western observers; but even so there rings through Mishima’s work an exceptionally single-minded fascination with suicide.

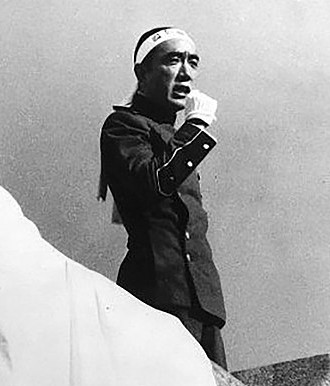

As he approached the end of his life, Mishima espoused a reactionary Japanese politics based on the traditional divinity of the emperor. The centerpiece of this project was a paramilitary society of like-minded young men, in which his own more-or-less open homosexuality certainly played a part. Mishima met his explosive destiny in 1970, when, at the age of 45, he and a handful of disciples seized a high-ranking officer in the Japanese Self-Defense Forces as a hostage. He exhorted an assembly of soldiers to join with him in restoring the emperor, but was answered by jeers. Having failed, he committed suicide by seppuku.

Whatever else may be said about him, Mishima’s death proved that he possessed tremendous force of both will and imagination. His final act can be understood as a piece of performance art, a pageant for the ages. It was an acting-out of his fiction in its every detail, from the sudden, frenzied violence of the commandant’s seizure to the last gory spurts of his own blood. Mishima’s imagination was powerful enough to reify his art.

At the same time, he was overcome by it. If Mishima had succeeded in his aim – if the soldiers had been roused to action by his address, and swept the emperor back to divine power atop a wave of nationalistic zeal – it would have been the conclusion of a great story, but it would not have been his story. Mishima’s protagonists do not achieve their aims, unless their suicides count. They do not meet with victory in their struggles. In the end, Mishima could not imagine what winning looked like. It is precisely in the jeers of the soldiers that the special artistic touch of Mishima is to be detected. He himself fell victim to the same baleful doom he had already envisioned so many times in his writing. He carved the groove in which he was to run, and its end was always clear in his sight.

In the end, Mishima did not believe that his art contained any beauty with the power to sustain – but then it is by no means clear that he ever did. His work, with its adoration of destruction, is as opposed to beauty as the most banal Western postmodernist’s; he is simply more explicit about it. Mishima’s artistic career, perhaps more than any other writer’s, is a monotonic development of a single idea. He spent his life honing and sharpening it to a lethal point, and then killed himself with it.

Recently, Mishima has become a guiding star for the nascent post-Christian Right in America. As a reactionary, Mishima was dedicated to a vision that had already been rejected by his contemporaries. In this particular case, we may be thankful for his failure; it is not hard to argue that the world is better off without the demonic ferocity of imperial Japan. But the failure of his political project illustrates an important lesson. Cries to “RETVRN”, however self-aware or layered with irony, are intrinsically insufficient. Extinct orders, however monstrous or idyllic, were extinguished because they became maladapted to their circumstances. To restore what was good about them, the causes for their extinction must be clearly identified and addressed. It was foolish for Mishima to call for the restoration of a divine emperor in a Japan still practically under American occupation, just as it is foolish for the Distributists to clamor for a restoration of the medieval guild system in a contemporary industrial economy, or whatever the American Solidarity Party imagines it is trying to achieve. The difference is that for Mishima, the foolishness was most of the point. The lesson of Mishima is that reaction is an excellent pretext for a glorious suicide. As a vision for the future, it is sorely lacking.

2 thoughts on “Yukio Mishima and the Suicide of Artists”